Category: the present moment

shine on, you crazy diamond

Wellbeing, peace and happiness are hidden in plain sight, in the ever-present flow of experience itself, always right here and right now. I recently completed an intensive, 30 day silent meditation retreat in California following a…

Written by

sit quietly and observe your thoughts

This simple practice helps release unhelpful preoccupations that creep into your mind space as you sit quietly and observe your thoughts. As we release these unhelpful preoccupations, we find less craving for distraction hits like the…

Written by

softly, as in a morning sunrise

Meditation shows me my burdens were mostly imagined. But even imaginary ones can carry real emotional weight. I remember this cartoon I saw perhaps 20 years ago while waiting at a doctor’s office. A woman and…

Written by

on having no goals

As you set out on your meditation journey- avoid aggressive self-improvement. There isn’t anything to improve; the present moment is just fine as it is. One of the trickiest aspects of mindfulness meditation is the whole…

Written by

present moment happiness

As we soak in the healing waters of the present moment, the chasms between sacred and mundane, bearable and unbearable, dissolve. We live in uncertain times. Putin’s recent cold threat of a nuclear strike against Ukraine,…

Written by

practicing present moment awareness

The practice of present moment awareness shows us that whatever we are dealing with does not define us. Difficult stuff comes up, but it doesn’t diminish our well-being. Maybe right now as you are reading this,…

Written by

Don’t worry about progress

Progress happens when you don’t think about it. I was struck by a poem the other day while reading a new translation of the Therigatha, a small book of verse compiled in the beginning of the…

Written by

letting go of wanting happiness

Folks who meditate in order to feel better often find the opposite. Eventfully they see that it’s the letting go of the wanting of happiness, that actually brings it! I can begin to answer by sharing…

Written by

mindful listening

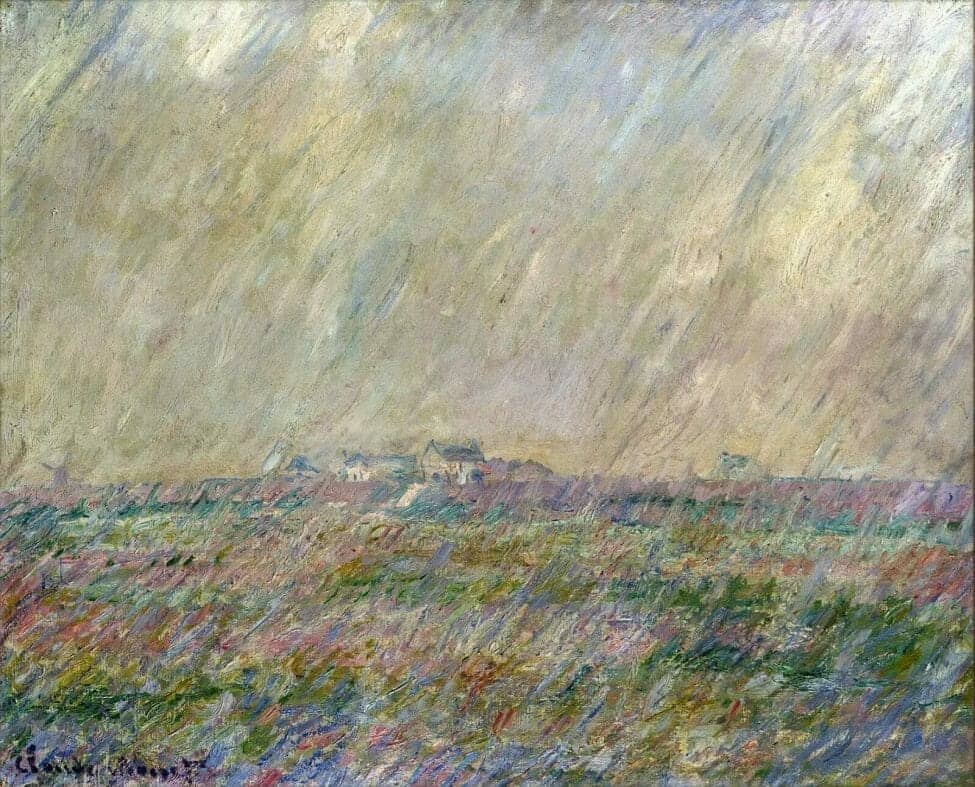

There is something unspeakably beautiful about mindful listening to the rain. Not just hearing the rain, but really listening. I love the way Thomas Merton describes mindful listening. One morning he awoke to the rain in…

Written by

mindfulness meditation practice & the tiny purple flowers by the side of the road

We already have what we need – “your brain and your heart are your temples, and your philosophy, kindness.” It seems many of us get hooked by trying to get somewhere in our mindfulness meditation practice. …

Written by