Category: intimacy

the simplicity of mindfulness

One clear thread weaves through our practice: the simplicity of mindfulness. We are acquainted with complication. We know the feeling of being tangled, knee-deep in old resentments or lost in anxiety, listening to the compelling arguments…

Written by

living into what cannot be solved

Mindfulness allows us to live into all that cannot be solved. It’s also a gateway to equanimity, the peace of the present moment. The other day, I listened to a podcast of an interview with Frank…

Written by

to live wisely, and able to love

This is our work: to live wisely, not in contention with anything, and able to love. What does it mean to practice Dharma in the home stretch of 2023, with all the wars, hate crimes, refugee…

Written by

appreciate your life

We savor our life just as it is, messy, littered with abandoned to-do lists and unfulfilled expectations. We appreciate our life now, we’re not just managing it. When asked about the fruit of meditative life,…

Written by

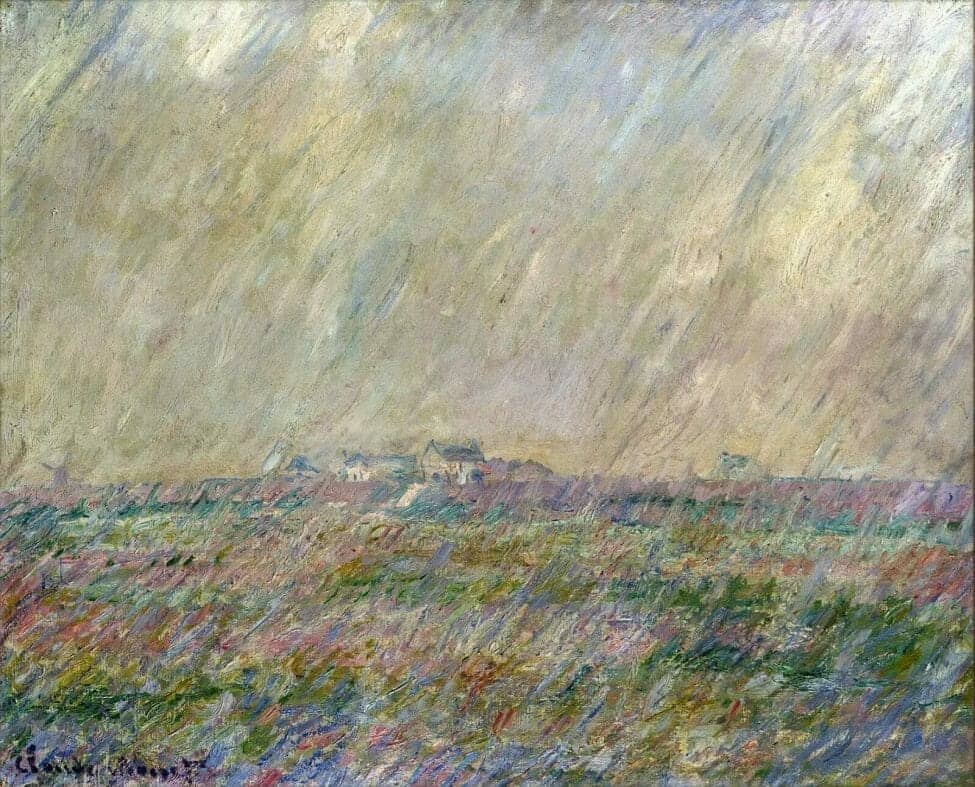

mindful listening

There is something unspeakably beautiful about mindful listening to the rain. Not just hearing the rain, but really listening. I love the way Thomas Merton describes mindful listening. One morning he awoke to the rain in…

Written by

why I stopped making new year’s resolutions

I decided to not make any new year’s resolutions. Well, except maybe one. I resolve to just be myself. I always felt making a set of resolutions meant needing to improve myself, be better at something,…

Written by

intimacy with all things

When asked about the fruit of the spiritual life, the 13th century Japanese monk Dogen Zenji replied: “Enlightenment is intimacy with all things.” Mindfulness allows us to intimately see a flower, or watch a sunset, or…

Written by